The classical Japanese season words have hundreds of years of cultural buy-in from Japanese haijin. Those of us who study saijiki know that each season has its own word associations that are deep and subtle. The season words (kigo) not only place us in the season as a whole, but also indicate where in the season (early, middle, late) the poem lives. Some classical terms seem universal. For example, “snow” is a well-established winter haiku.

alpine winds

the soft timbre

of fresh snowMona Bedi, Autumn Moon 9:1

Most people who live in temperate zones in both the Northern and Southern hemispheres experience snow at some point during their winter months. (Note that the hemispheres have their winter and summer months reversed.) While amounts vary, snow occurs frequently enough in winter that we have more or less global buy-in about the term as a winter kigo.

While season words have well-established associations, they are still malleable. For example, in the classical tradition, “moon” is an autumn kigo. Poets have to modify the word, or use a different kigo entirely, in order to place the poem in another season.

the end of visiting hours cold moon

ang katapusan ng oras ng pagbisita malamig na buwan

Alvin B. Cruz, Autumn Moon 9:1

In Alvin’s haiku above, “cold moon” places us in winter; the cold moon is the full moon that appears in December (https://www.almanac.com/full-moon-december).

The malleability of season words allows us to recognize that natural and wild phenomena have the potential to appear all year. The moon doesn’t just appear in autumn, so we have evolved our poetic language to write about the moon in all seasons. Likewise, while it can be difficult to fathom, no single weather phenomena belongs to a single season. I struggle to imagine snow in winter, but in high-latitude northern countries such as Iceland, snow can appear in the summer months. While it’s not frequent or heavy, it’s also a documented phenomena. Even in lower-latitude countries, mountainous regions can experience snow in the summer; we can see this throughout Europe and Asia, as well as South America. While I’m not likely to experience summer snow in my life (owing to my dislike of cold and tendency toward serious altitude sickness), I couldn’t realistically read a haiku that included the term “summer snow” and outright declare it preposterous. While season words such as snow seem universal, the experience of snow at different points in the year can never be truly universal, as said experience is dependent on fluctuations in geography and climate.

I’ve written frequently about how, as a child, I felt out of step with the seasons as they were dictated by the Gregorian calendar. Of course, I didn’t have a sense that different calendars had been used throughout history. I didn’t even have a concept that people operated within different calendar systems in contemporary society; my first exposure to that was when I was dating my first husband, and would occasionally attend shabbat services with him. That was where I learned about the Jewish liturgical calendar, which was operating on its own sense of time.

The Gregorian calendar creates a boundaried approach to the seasons, meaning that it uses the equinoxes and solstices as hard stop and end points. The upcoming spring equinox will signal a hard stop to winter and a hard beginning to spring. Meanwhile, as I drove to work this morning, yellow daffodils lined the grass of my exit ramp. There are buds on the crab apple and maple trees. Spring has definitely arrived in St. Louis . . . but we’re likely to get one more hard freeze later in the month. I might be wearing sandals today, but I know the remains of winter lurk in the atmosphere. Because of the hard seasonal boundaries it creates, the Gregorian calendar has value for the scientific community, but the organizational schema does not allow for the malleability of seasonal change. It creates a fixed view of when seasons start and stop and, in my opinion, that tends to create a sense of seasonal ownership versus seasonal association. When we operate exclusively with a fixed, boundaried view of the seasons, we limit our perception and our writing. Snow can only belong to winter . . . though if you’ve ever lived in Cleveland1 (or worse), you know perfectly well it can show up in spring.

While not everyone who is raised exclusively under the Gregorian calendar will inherently develop a fixed relationship to the seasons, it certainly happened to me. This is why I could get frustrated and say, “It’s spring! It’s not supposed to snow on my birthday!” Well, when you live in Ohio, snow doesn’t care about the equinox or about spring birthdays. A fixed understanding of the seasons ultimately led me to a mental framework that frequently set me up for disappointment and also inhibited my approach to haiku. A malleable view of the seasons becomes even more important as the effects of climate change continue to unfold2. John can say, “It’s not supposed to be 90 degrees in October,” and while historically St. Louis might not have seen persistent 90-degree weather in mid-autumn, the concept of supposed to becomes less and less relevant as the climate destabilizes. If we are going to maintain whatever emotional equilibrium is possible during the current era, and also continue to be able to write season-based poetry, we need to leave room to allow for the changing seasons as they are, even as we resist the forces leading us toward our own destruction.

When I first began my study of saijiki, I found it difficult to operate within two calendars at once. The classical haiku calendar, which uses the solstices and equinoxes as the midpoints of the seasons, made more sense in relation to my lived experience. However, the Gregorian calendar guides the country in which I live. Sometimes, it is deeply frustrating to see people celebrating “the first day of spring” when spring has been evident for weeks. I get irrationally annoyed that The Old Farmer’s Almanac – an inherently agricultural text! – eschews the preindustrial boundaries of the seasons and adopts the Gregorian seasonal boundaries. However, my exposure to different religious traditions helped me understand that all over the world, people adhere to different calendars. I’ve of course learned about the Jewish liturgical calendar; life in St. Louis has also exposed me to the Catholic liturgical year, as well as the Orthodox Christian year. In my own personal studies, I’ve learned about Hindu and Buddhist calendars as well. Most people with a specific religious or cultural identity navigate their specific calendar along with the Gregorian one. There’s no reason why a haiku poet can’t do that as well.

Likewise, my understanding of season words and what they mean cannot be limited to my experiences living in the Midwest and the American South my entire life. I have to recognize that my experience of summer will never be the same as the experience of someone living in Iceland. The world is too big to contain any individual’s limited knowledge of seasons. In fact, it’s too big to contain any one saijiki’s attempts to categorize the seasons. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t study saijiki. Rather, we have the saijiki as a foundation that guides our experience, but doesn’t dictate it. After all, even the strictest saijiki won’t refuse to let poets write about the moon in the spring.

As I wrap up this post, I’m reminded of this enduring haiku from Shiki:

for me going

for you staying—

two autumns

This haiku points to the individual experiences of two friends who will spend autumn in different regions. Today, it has me thinking about how there are in fact innumerable autumns (and winters and springs and summers). That is not to say that we should take a purely individualistic approach to the seasons, but rather that we should recognize the incredible variety within collective experience. Within the St. Louis area, we will all experience redbud flowers, bird migration, and the nerve-wracking experience of tornado season; due to geographic differences even in a relatively small area some of us will be more prone to flooding than others. Even in a single city, there is variability within each season. As haiku poets, it’s imperative that we study saijiki, understand our environmental foundations, and also leave room for the broader malleability of seasonal experience.

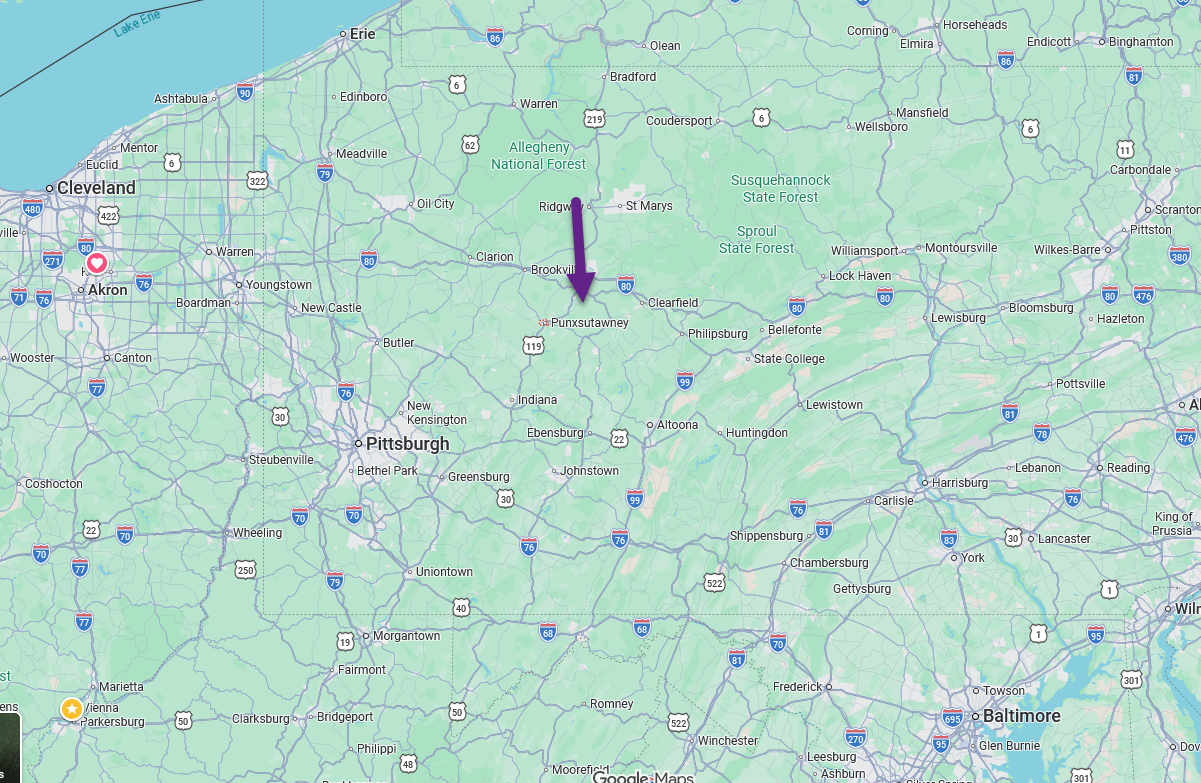

1I will always have a fondness for Cleveland, but not the lake effect snow.

2This is not to say that we shouldn’t do what we can to combat climate change, but when the AI bubble hasn’t burst and the US is rolling back environmental regulations, well . . .